- La Feria Community Holds Succesful Business Mixer Event

- Little Nashville to Take Place in Downtown Mercedes

- Lions Basketball Captures District Gold

- La Feria ISD Students Compete in Regional Chess Tournament

- Lions End First Half of 32-4A on a High Note

- La Feria ISD Held Another Successful Parent Conference

- Strong Appearance for Lions at Hidalgo Power Meet

- LFECHS Students Get to Meet Local Actress

- Students Participate in Marine Biology Camp

- Two LFECHS Students Qualify for All-State Band

The Early Days of La Feria – The Coahuiltecans

- Updated: February 20, 2015

The city of La Feria is celebrating its 100th year anniversary and to commemorate the occasion we are digging deep into our archives each week to bring you images and stories from La Feria’s colorful past.

The city of La Feria is celebrating its 100th year anniversary and to commemorate the occasion we are digging deep into our archives each week to bring you images and stories from La Feria’s colorful past.

The Early Days of La Feria

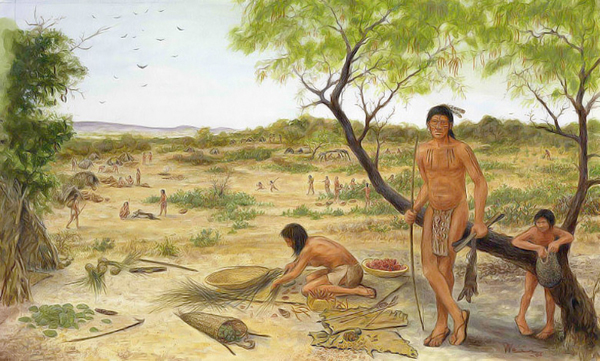

Native South Texans – The Coahuiltecans

Coahuiltecans were small roving bands of natives thought to have lived in the South Texas plains for thousands of years.

The name given to the Coahuiltecans by the Spaniards derives from Coahuila, the Mexican state in which some of them lived. The word Coahuila derives from a Nahuatl word.

The Coahuiltecans lived in the flat, brushy, dry country of southern Texas, roughly south of a line from the coast of the Gulf of Mexico at the mouth of the Guadalupe River to San Antonio and hence westwards to around Del Rio. They lived on both sides of the Rio Grande. Their neighbors along the Texas coast were the Karankawa, and inland to their northeast were the Tonkawa, both tribes possibly related by language to some of the Coahuiltecans. To their north were the Jumano and, later, the Lipan Apache and Comanche. Their indefinite western boundaries were the vicinity of Monclova, Coahuila, and Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, and southward to roughly the present location of Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas, and the Sierra de Tamaulipas. People of similar hunting and gathering livelihood lived throughout northeastern Mexico.

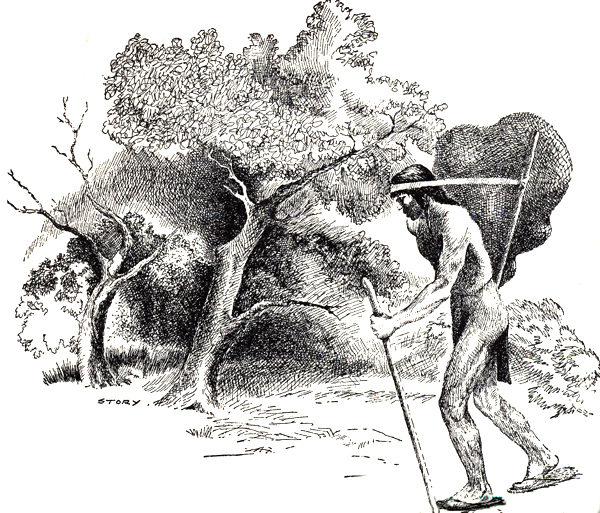

A South Texas native carries a heavy pack of supplies in a fiber net supported by a tump line across his forehead. Drawing by Hal Story.

Although living near the Gulf of Mexico, most of the Coahuiltecans were inland people. Near the Gulf for more than 70 miles (110 km) both north and south of the Rio Grande, there is little fresh water, which limited the opportunity to live near and exploit coastal resources. Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and his three companions were the first Europeans known to have lived among and passed through Coahuiltecan lands in the early 1530s. In 1554, three Spanish vessels were wrecked on Padre Island. The survivors, perhaps one hundred persons, attempted to walk southward to Spanish settlements in Mexico. All but one were killed by the Indians.

In the early 1570s the notorious conquistador Luis de Carabajal y Cueva campaigned near the Rio Grande, ostensibly to punish the Indians for their attack on the shipwrecked sailors, more likely to capture slaves. In 1580, Carabajal, governor of Nuevo Leon, and a gang of “renegades who acknowledged neither God nor King” began conducting regular slave raids along the Rio Grande. The Coahuiltecans were not defenseless. They often raided Spanish settlements, and they drove the Spanish out of Nuevo Leon in 1587, but they lacked the organization and political unity to mount an effective defense when a larger number of Spanish settlers returned in 1596. Conflicts between the Coahuiltecan peoples and the Spaniards continued throughout the 17th century. Slavery was replaced by the encomienda system which, although exploitative, was less destructive to Indian societies than slavery.

Smallpox and measles epidemics were frequent. The first recorded epidemic in the region was 1636-1639 and it was followed regularly by other epidemics every few years. A 17th century historian of Nuevo Leon, Juan Bautista Chapa, predicted that all Indian and tribes would soon be “annihilated” by disease and listed 161 bands that had once lived near Monterrey but had disappeared.

However, Spanish expeditions still found large settlements of Coahuiltecans in the Rio Grande delta and large-multi-tribal encampments along the rivers of southern Texas, especially near San Antonio. Mission San Antonio de Valero (the Alamo) was established in 1718 to evangelize among the Coahuiltecan and other Indians of the region, especially the Jumano.

Four additional missions were soon established. The Missions seems to have had some support among the Coahuiltecans as they looked to the Spanish for protection from a new menace, Apache, Comanche, and Wichita raiders from the north. The five Missions had about 1,200 Coahuiltecan and other Indians in residence during their most prosperous period from 1720 until 1772. That the Indians were often dissatisfied with their life at the Missions is manifested by the frequent “runaways” and desertions.

Spanish settlement of the lower Rio Grande Valley and delta, the remaining demographic stronghold of the Coahuiltecans, began in 1748. Fourteen different bands were identified as living in the delta in 1757. Overwhelmed in numbers by Spanish settlers most of them were absorbed by the Spanish within a few decades.

Coahuiltecan lifeways, in the words of one scholar, “represent the culmination of more than 11,000 years of a way of life that had successfully adapted to the climate and resources of south Texas.” They shared the common traits of being non-agricultural and living in small autonomous bands with no political unity above the level of the band and the family. They were nomadic hunter-gatherers, carrying their meager possessions on their backs as they moved from place to place to exploit sources of food that might be available only seasonally. At each campsite, they built small circular huts with frames of four bent poles which they covered with woven mats. They wore little clothing. At times, they came together in large groups of several bands and hundreds of people, but most of the time their encampments were small, consisting of a few huts and a few dozen people. Along the Rio Grande the Coahuiltecans lived more sedentary lives, perhaps constructing more substantial dwellings and utilizing palm fronds as a building material.

The Coahuiltecans had good bows and arrows and hunted small game. Occasionally bison strayed into their region from the Great Plains to the north. They also subsisted, during times of need, on worms, lizards, ants, and undigested seeds collected from deer dung. They ate much of their food raw, but used an open fire or a fire pit for cooking. Most of their food came from plants. Pecans were an important food, gathered in the fall and stored for future use. In summer, large numbers of people congregated at the vast thickets of prickly pear cactus south-east of San Antonio where they feasted on the fruit and the pads and interacted socially with other bands. They cooked the bulbs and root crowns of the maguey, sotol, and lechuguilla in pits and made flour out of mesquite beans. Most of the Coahuiltecans seem to have had a regular round of travels in search of food. The Payaya band near San Antonio had ten different summer campsites in an area 30 miles square. Some of the Indians lived near the coast in winter and journeyed 85 miles inland to exploit the prickly pear cactus thickets in summer. Fish were perhaps the principal food item for the bands living in the Rio Grande delta.

Little is known about the religion of the Coahuiltecans. They came together in large numbers on occasion for all-night dances called mitotes in which peyote was eaten to achieve a trance-like state. The meager resources of their homeland led to intense competition and frequent, although small scale, warfare.

RESOURCES & FURTHER READING

The Texas Coahuiltecan Indian Groups by R. E. Moore – www.texasindians.com/coah.htm

Texas State Historical Association – www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/bmcah

University of Texas at Austin College of Liberal Arts – Who Were the “Coahuiltecans”? www.texasbeyondhistory.net/st-plains/peoples/coahuiltecans.html

Do YOU have any photos, books, or stories that might help us piece together La Feria’s storied history? If so please email us at news@laferianews.net or call our office at 956-797-9920 and let us know!

One Comment